Caught in the ring of ill-fated love: November performances at Deutsche Oper Berlin

Caught in the ring of ill-fated love: November performances at Deutsche Oper Berlin

As I do each year, to escape the national gloom and an overdose of paraffin-scented incense, I decided to leave Poland for the first weekend of November. On the recommendation of Gniewomir Zajączkowski, I traveled to Berlin, where Deutsche Oper was presenting two captivating operas: “Francesca da Rimini” and “Tristan und Isolde.”

Deutsche Oper has a fascinating history: its original building, opened in 1912 as the Deutsches Opernhaus, was destroyed during the war. The current one was inaugurated in 1961. Designed by Fritz Bornemann, it became one of the most important symbols of West Berlin’s cultural reconstruction. During the city’s division, it served as the main representative opera house of West Berlin, while the Staatsoper operated on the East side of the Wall.

The modernist architecture is austere and functional, without theatrical embellishments, designed primarily for audience comfort. The auditorium, divided into stalls and two balconies, is spacious with approximately 1,860 seats. On the sides are distinctive protruding sectors reminiscent of modern boxes. The seats are comfortable, the space wide and clear, and the hall designed to provide excellent visibility from nearly every seat. The foyer, reflecting 1960s aesthetics, exudes simple elegance and is flooded with natural light. Bars are open before the performance and during intermissions, and a restaurant adjacent to the opera offers pre- or post-show reservations. This is not a palace-like theater of marble and gold, but a functional house designed for comfortable engagement with the art rather than for celebrating splendor.

The first performance I attended was the rarely staged verismo masterpiece by Riccardo Zandonai, “Francesca da Rimini.” The production premiered in 2021, during the pandemic – without an audience and streamed online. The first live audience performance took place only two years later. In that premiere, the main roles were performed by Sarah Jakubiak, Ivan Inverardi and Jonathan Tetelman. I had been hoping to see the first two performers again this time. Unfortunately, due to illness, Sarah Jakubiak was replaced by Ekaterina Sannikova. I was disappointed, as I had eagerly anticipated her interpretation, but health comes first. The production blends elements of verismo, modernism and impressionism, with echoes of Wagner and Strauss. The music is dense, passionate, sensual, and at times hypnotic. Zandonai builds a world full of emotional and psychological nuance, and the title character is one of the most boldly drawn female roles of early 20th-century opera strong, desirous, fully aware of her own passions. Later, Puccini would push the emancipation of operatic heroines even further.

It is not a standard repertoire piece for many reasons: the expanded orchestra, enormous vocal demands, complex acting tasks, and the need to stage a believable story of forbidden love set against political conflict. Such demanding material is reserved for the best artists, making theaters approach it with caution.

Director Christof Loy, in collaboration with Johannes Leiacker (set design) and Klaus Bruns (costumes), abandoned traditional staging grandeur. Instead of monumental decorations, the production features an elegant, understated villa and a landscape that evokes the atmosphere of Southern Europe rather than depicting it literally. Loy avoids literalism. The costumes are neither contemporary nor historical – the action is suspended in time, and the director guides the characters almost cinematically, focusing primarily on their emotions. The chorus sings offstage, replaced on stage by actors in minor roles. This simple yet highly effective approach builds intimacy and naturalness.

Ekaterina Sannikova’s Francesca balanced lyricism and submission with sudden, expressive independence. Vocally solid though occasionally strained, nearing a shout. Paolo, performed by Rodrigo Garulla, delivered a spinto tenor with solid volume and projection. Gianciotto, sung by Ivan Inverardi, captivated with the warm baritone, yet could also be menacing and ruthless. The quartet of Francesca’s maids was exquisite – a delicate, lyrical counterpoint to the darkness and brutality of the Malatesta court. The young women acted as Francesca’s inner voice, reflecting her emotional states. Beautifully harmonized voices – Elisa Verzier, Arianna Manganello, Martina Baroni and Lucy Baker – created one of the evening’s most atmospheric layers. The orchestra, conducted by Iván López-Reynoso, brought out the opera’s impressionistic light, color and sensuality. Musical execution was meticulously crafted – kudos to the orchestra.

The production was very good, though not groundbreaking. It does not alter the status of “Francesca” or restore it to the global stage with the force of a triumphant comeback. It remains a beautiful gem for connoisseurs, intelligently staged and full of musical beauty. I watched it among friends with mixed reactions: some left after the first act, while others were enthralled. I felt the main roles lacked a certain magnetism, particularly in Act III, which dragged for me despite the musical beauty. Still, I am glad to have experienced it live and now plan to revisit the 2021 streamed version to finally hear Sarah Jakubiak and Jonathan Tetelman.

The following evening, I attended the premiere of Richard Wagner’s “Tristan und Isolde,” directed by Michael Thalheimer. This marathon production, for the patient, began at 4:00 p.m. and lasted 5 hours and 10 minutes. It was a co-production with the Grand Théâtre de Genève, where it premiered the previous season.

“Tristan und Isolde” is a groundbreaking work. After the grand, spectacular operas of the 19th century, Wagner opens a completely new chapter in music and theater. He abandons external pomp in favor of internal tension, psychological truth and a continuous flow of emotion – a wholly different form of storytelling with novel expressive means.

An extraordinary new cast at Deutsche Oper made the journey to Berlin worthwhile. The title roles were performed by Clay Hilley and debutante Elisabeth Teige. Hilley possesses a highly sought-after Wagnerian heldentenor, with a beautiful, rich timbre and exceptional vocal technique. Unlike some of his peers, he sings even in dramatic passages rather than shouting. His Tristan is naïvely happy, genuinely in love, natural and straightforward, without a trace of affectation. Teige, in the opening scenes, is dramatically fierce, sharp and uncompromising; her soprano cuts through the air like a razor. Later, after drinking the love potion, her character transforms, and her voice gains lyricism and softness. Together, they delivered a transcendent duet in Act II, seemingly suspended in time. Act III belonged to Hilley, who conveyed Tristan’s final moments with emotional and vocal precision.

Irene Roberts performed Brangäne with a rich, velvety mezzo and strong stage presence. Her Act II passages, performed from a balcony, were particularly effective, enveloping the audience in sound and fostering a remarkable interaction between the stage and the auditorium.

As Kurwenal, Thomas Lehman impressed with a rich, powerful baritone, vocally splendid and convincingly acted. Georg Zeppenfeld delivered a masterful King Mark – majestic, deep bass and dignified, restrained interpretation that moved the audience profoundly. Both the male chorus and the Deutsche Oper orchestra, under music director Sir Donald Runnicles, performed with discipline and emotional tension.

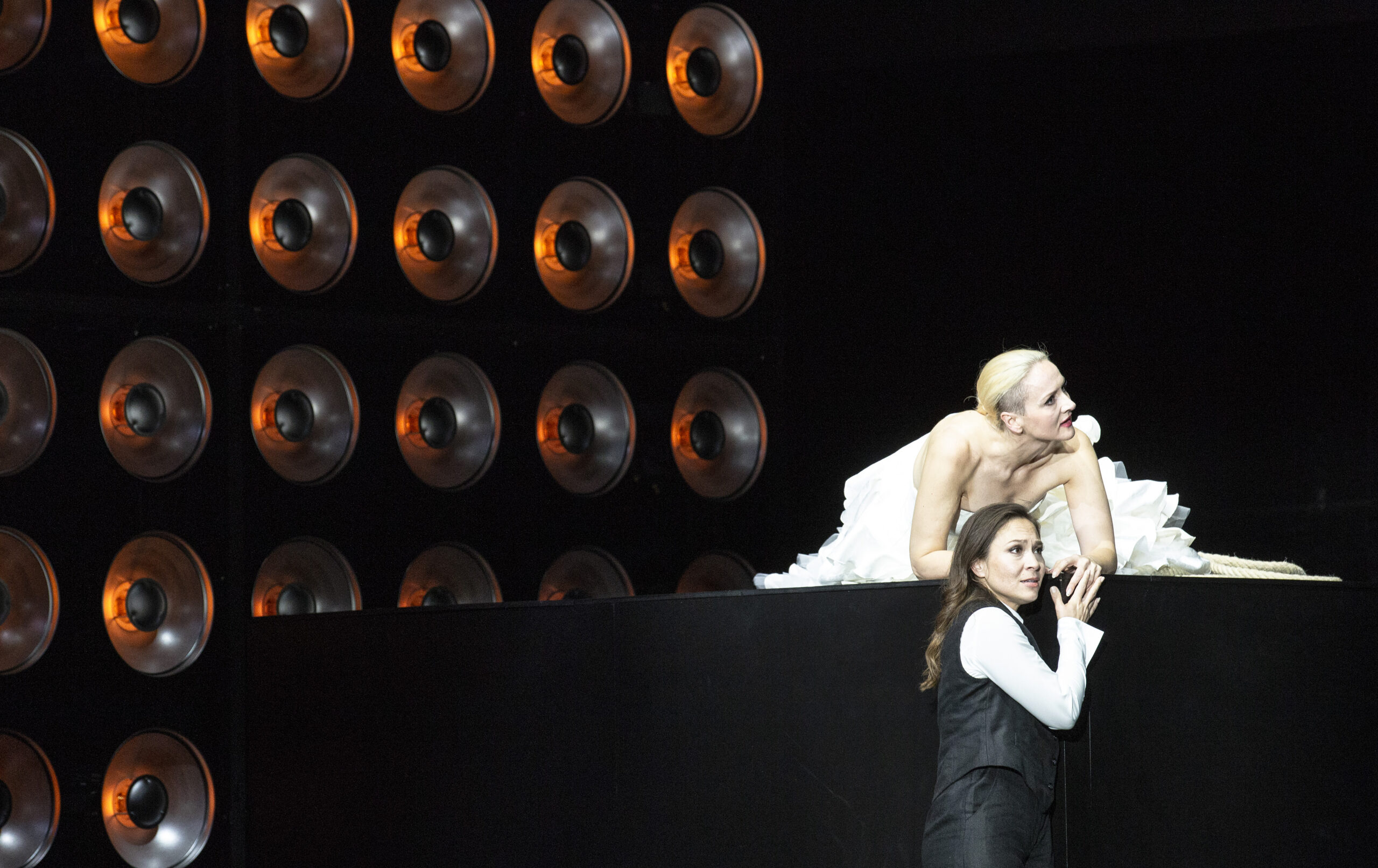

The staging received mixed reactions. The sophisticated, minimalist approach seems more suited to Wagner connoisseurs than a general audience. Director Thalheimer, with set designer Henrik Ahr and costume designer Michaela Barth, opted for radical minimalism, reducing the design to essentials. In the first two acts, a blackened stage is dominated by a wall of 260 lamps, their glow shifting with the characters’ emotions – warm amber for love, harsh white at tense moments, sometimes blinding, sometimes fading into darkness. A movable platform carries part of the action across the stage.

Act III is the most visually striking: the lamp wall rises above the stage as the wounded Tristan emerges, dragging a rope toward the audience, accompanied by the melancholic English horn solo – a symbol of Tristan’s longing and pain on the Cornish shore. The black-and-white costumes are simple and unpretentious, aligning with the overall concept.

For Thalheimer, day, light and white embody the human, structured, and comprehensible realm, whereas darkness and black evoke what defies reason – the transcendent, mystical love of Tristan and Isolde, attainable only beyond life. The performance concludes with Elisabeth Teige’s magnificent “Liebestod.” Despite the static staging, the musical and vocal execution was remarkable, leaving the audience with the impression of having witnessed something extraordinary, even during moments of fatigue or impatience.

Practical Information for Visiting Deutsche Oper Berlin:

How to get there: Deutsche Oper Berlin is located at Bismarckstraße 35 in Charlottenburg. Easiest access via U-Bahn: U2 (station “Deutsche Oper”) or U7 (station “Bismarckstraße”). From Berlin Hauptbahnhof, about 15 minutes by metro or train. From Berlin Brandenburg Airport (BER), approximately 45–55 minutes via public transport (S-Bahn + U-Bahn).

Tickets: Best purchased in advance via the opera website: www.deutscheoperberlin.de. Online system allows selection of specific seats. No standing areas; cheapest seated tickets usually start around €20.

Discounts & Cards: The Deutsche Oper Card (€75 per season) offers 30% off two tickets for the holder and a companion. Last-minute tickets and student discounts (typically 50%) are also available.

Programs: Printed programs (€6) available in the foyer, including cast, libretto synopsis and essays.

Surtitles: Displayed above the stage in German and English.

Bars: Several bars in the spacious foyer serve drinks and snacks. Beer €5, coffee €3.50. Pre-ordering is recommended to avoid queues during intermission.

Shop: Small stand in the foyer sells CDs, books, and souvenirs related to Deutsche Oper Berlin’s repertoire and history.