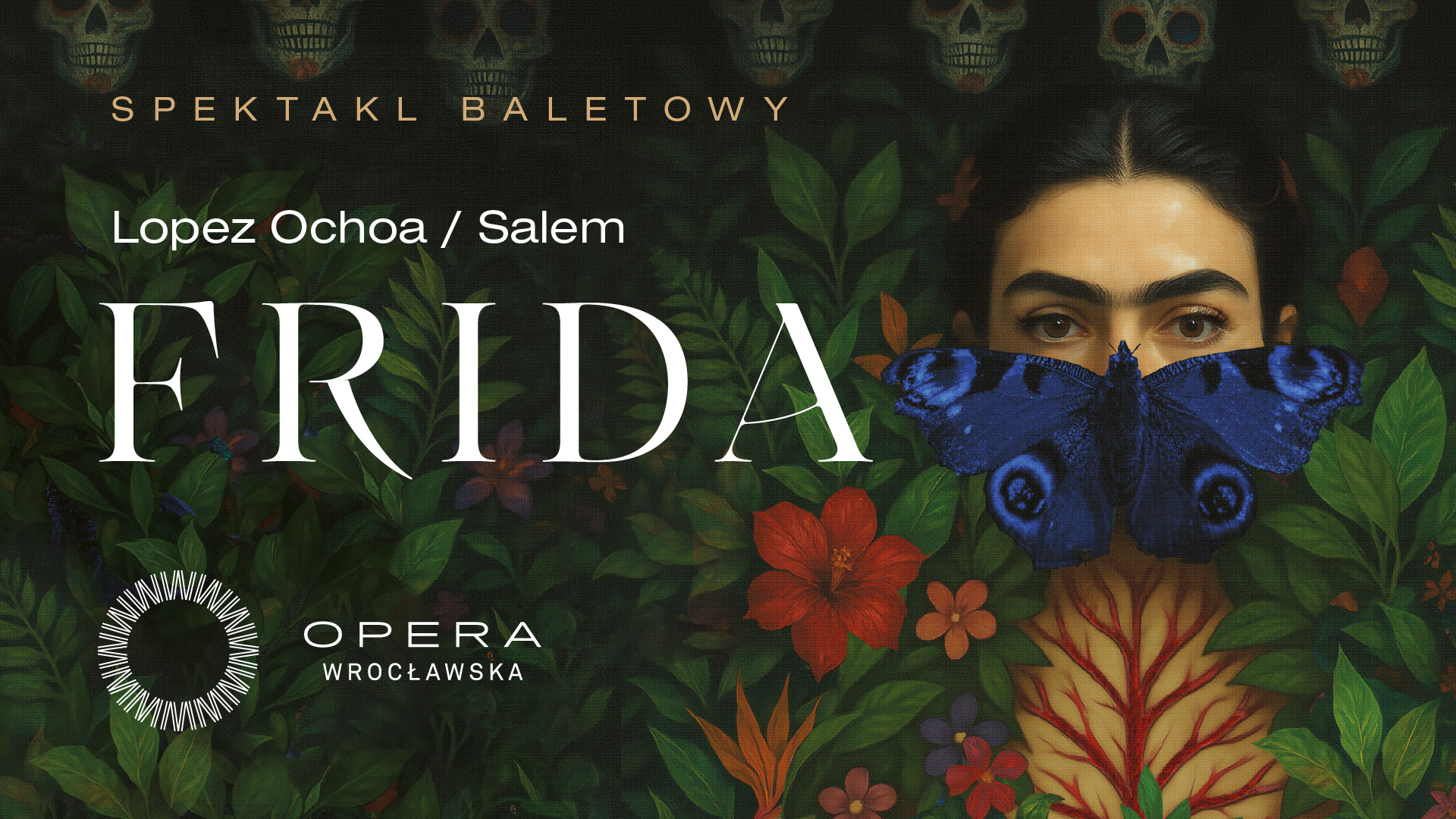

Dancing life: a story of Frida Kahlo told through movement

Dancing life: a story of Frida Kahlo told through movement

I walk through the empty corridor of the Wrocław Opera House. Here, silence has a scent — the touch smeared across a golden handrail, the gentle echo of music that hasn’t yet begun. Light filters through tall windows, dissolving on the walls like watercolor. I stop by the door of the ballet rehearsal room. Behind it — a silence that isn’t mute. It’s focus. I open the door. Before me stand two young women, seemingly delicate, light, almost translucent. And yet in motion, they hold a force that cannot be contained. Their bodies don’t just dance — they speak. Phoebe and Carola. Two Fridas. Two perspectives, two sensibilities, one spirit.

I follow the sound. In the audience, off to the side, sits Peter Salem. A composer. Attentive, warm. He radiates a calm that defies every myth of pre-premiere tension. He watches the movement on stage with a gentle smile. Our conversation happened on a different day, but as I think of it now, it blends seamlessly with this image. Peter spoke softly then, without emphasis: Sounds don’t need to be pretty. They need to be true. To carry pain, hallucination, narrative. Their impact lies in how challenging they are to absorb. I thought: this is what Frida must be. Not easy. Not smooth, but authentic. Not an ornament — a wound. And that’s exactly the Frida they are creating here. Step by step. Breath by breath.

The story begins with the Day of the Dead. A young Frida Kahlo — full of life, bright, laughing — is suddenly immobilized. The accident changes everything. Confined to bed, she discovers painting. She is guided by the Deer — her alter ego, a shadow that never leaves. Through him, Frida walks through her self-portraits, encountering nine male Fridas. The Tehuana costume becomes her new skin — cultural, feminine, defiant. And then — Diego. Love. Betrayal. Frida’s words return like a mantra: I suffered two grave accidents in my life. One in which a streetcar knocked me down… The other accident is Diego. The second was worse.

In the second act, we return to Mexico with Frida. She paints “The Two Fridas,” “The Broken Column.” She cuts her hair in protest. She dies in the arms of the man who was both her great love and her greatest curse. Małgorzata Dzierżon, head of ballet at the Wrocław Opera, aware of the local audience’s needs, remains open to contemporary ideas, sensing that what people seek is narrative: Frida isn’t a biography. It’s a portrait. Deep. Moving. Emotional. And indeed — this performance doesn’t tell a story, it transports. It’s not a biography. It’s a state. A flight. Color. Pain. A scream through the body.

For Phoebe, this marks her debut in a leading role. She speaks about it with heartfelt emotion, but also with the maturity of someone who understands that trust is not just an honour — it’s a responsibility: I feel deeply grateful to be entrusted with this role. Frida feels close to me, even though I come from a different world. But she’s a complex, layered woman. And such closeness is only possible through movement, she shares. Meanwhile, Carola speaks with quiet determination, as if voicing something long held inside: It’s an honor and a challenge. I feel pressure — this is also my first big role — but I try to stay calm. Frida was strong, and I can learn that strength from her. They speak in one voice. But not because they’re the same — on the contrary, their strength lies in their difference. Without rivalry. We’re not split into primary and secondary casts. We’re a community. We support one another, Carola emphasizes. It’s rare. It’s beautiful.

Choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa sees Frida as a painting in motion: This isn’t a classical narrative. It’s the animation of painting. Frida wasn’t a surrealist — she painted life. We dance that life. When I ask Phoebe what’s the hardest part, she answers without hesitation: The emotions. Their intensity. Conveying pain, joy, anger, loss — in a way that brings the audience with us in every step. That’s the biggest challenge. But also the greatest meaning of dance.

In one scene, Frida takes the form of a deer. Her body, weakened and wounded, refuses to surrender. Black pointe shoes, antlers, the line of movement — everything is symbolic. The music doesn’t comment but empathizes. Peter Salem uses the sound of a bow drawn across a percussion plate. A metallic, almost glassy tone becomes a symbol of Frida’s physical pain. The sound returns each time the pain resurfaces. It’s like an echo from inside the body. Peter doesn’t compose illustration — he composes narrative. Music should not just tell the story — it should breathe with Frida, he explains. It should show her world — colorful, deep, at times hauntingly empty. A monochrome void gradually filled with color. These are not the sounds of Mexico. These are the sounds of Frida.

In this ballet, it is the music that dresses Frida’s portrait in every shade: melancholy, ecstasy, solitude, and courage. It reminds us that before Frida was a symbol, she was a woman — who suffered, who loved, who created despite her body. Her sound is not a sweet melody. It’s an internal pulse — uneven, fierce, real. And maybe that’s the point. Frida was a woman who turned emptiness into a world. Pain into art. Solitude into solidarity.

When the curtain falls and the orchestra fades, no one doubts: Frida hasn’t left. She remains. She floats above the stage, as if she truly had wings. As if she no longer needed feet to walk. Feet, what do I need you for when I have wings to fly? – she wrote. And in this ballet, those wings are hers. She rises above the opera house and lingers in the air long after the last note fades.

Who? What? Where? When?

“Frida” by Annabelle Lopez Ochoa | Music by Peter Salem

Wrocław Opera

June 7, 8, 10, 13, 14, 15, 2025