The Forgotten Icon of Pre-War Luxury – The Patria Hotel in Krynica-Zdrój

The Forgotten Icon of Pre-War Luxury – The Patria Hotel in Krynica-Zdrój

Built in the 1930s, “Patria” in Krynica-Zdrój remains a phenomenon to this day. Never before or since in Poland had there been such a grand investment initiated by an opera singer. Gifted with an extraordinary voice, Jan Kiepura used his talent not only to shine on stage but also to succeed in business.

Kiepura reached a level of stardom that few opera singers today could ever dream of. From Milan’s La Scala to the Metropolitan Opera in New York, between standing ovations, seas of flowers, and letters full of admiration, the tenor from Sosnowiec searched for his place on earth. He found it in the small spa town of Krynica, nestled in the picturesque Beskid Sądecki mountains, known as the “Pearl of Polish Spas.” It was here, at his initiative, that the “Patria” Hotel was built – a symbol of pre-war luxury and modernity.

Wyświetl ten post na Instagramie

The year is 1926. Jan Kiepura, fresh from his first international debut, is taking Europe by storm. London, Prague, Vienna, Berlin, and Budapest vie for his appearances, offering lucrative contracts. He is on the brink of his dream debut at La Scala, arranged with the support of Mario Puccini, the composer’s son, who has invited him to sing in “Manon Lescaut” and “Tosca.” Meticulous and enterprising, Kiepura records every fee from every performance in his letters to his parents and brother Władysław. He is already thinking about how to invest his earnings wisely – and profitably.

It was then that the idea of a hotel took shape, and he named it “Patria” (Latin for “homeland”). The first choice of location was nearby Żegiestów. But in 1927, persuaded by his friend, civil engineer Zygmunt Protassewicz (husband of film star Jadwiga Smosarska), Kiepura chose Krynica. Protassewicz argued in a letter: “Maestro! Krynica boasts unique mineral springs in Europe that cure infertility. The clientele is guaranteed. Invest in this charming spot, and you will surely succeed.”

Kiepura embraced the idea enthusiastically. Writing to his brother Władysław, he urged: “Build something European, not provincial, not just for Poland but for Europe, with the latest amenities. I will promote it abroad; we will attract foreigners and, at the very least, the Polish elite. Remember – build first-class. By law, the government must ensure the project is completed if any setbacks occur.” A true cosmopolitan, he understood that the success of his investment depended on its international character and appeal. As the wealthiest artist in Poland, he could afford to dream big. He purchased land at 35 Kazimierz Pułaski Street for $2.20 per square meter and set to work.

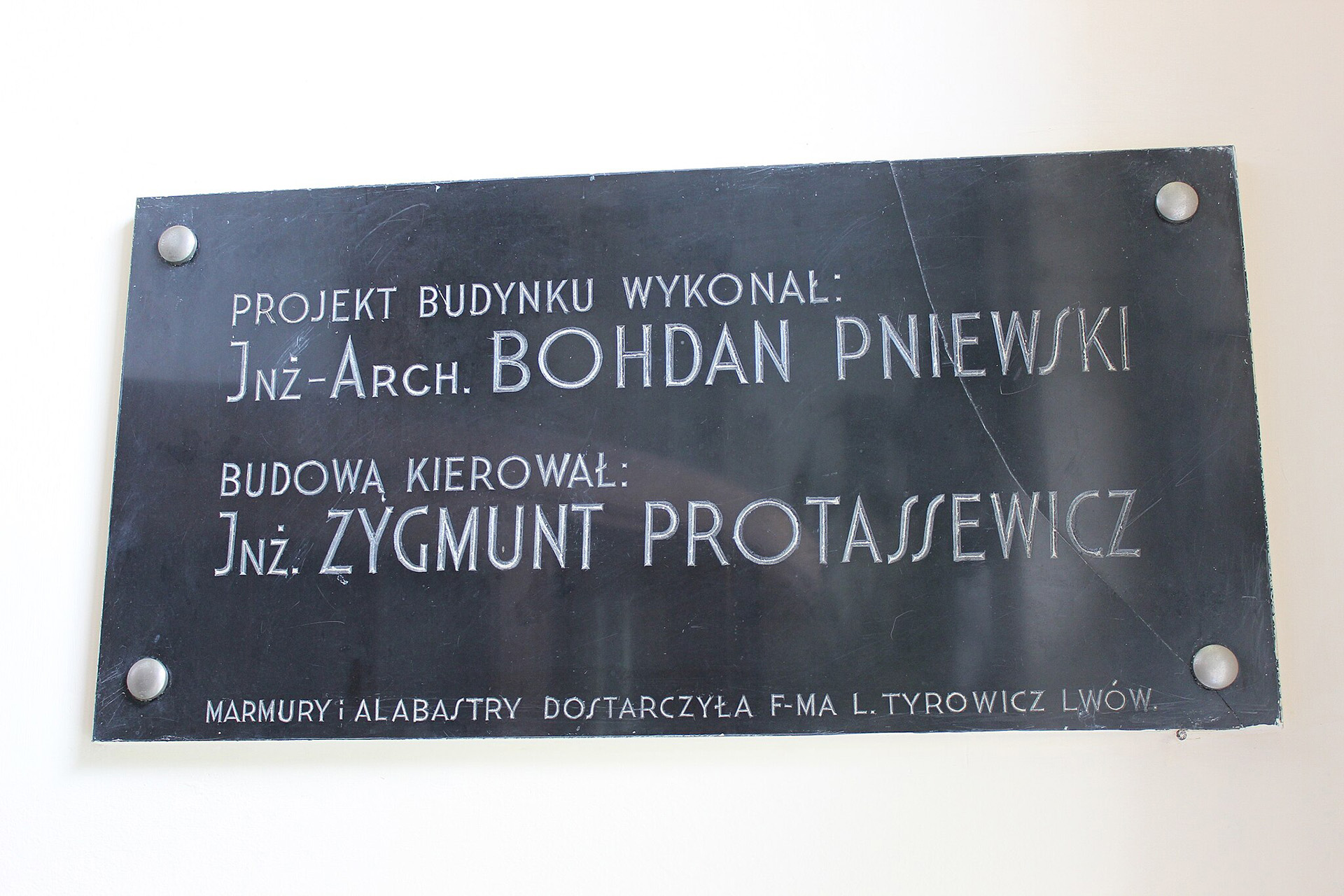

The architectural design was entrusted to Bohdan Pniewski, darling of Warsaw’s elites and a leading figure of Polish interwar modernism, whose works still grace the capital today. His elegant yet austere, ornament-free design was considered the epitome of modernity. Rounded corners, flat roof-terraces, and large windows gave the hotel a distinctive character. Andrzej B. Krupiński, author of the guide “Krynica and Its Surroundings,” described “Patria” as “one of the most interesting examples of functional architecture in Poland.” Spaciousness, ease of cleaning, and flexible interior layouts were key priorities.

Construction began in 1932, overseen by Protassewicz. Marble and alabaster, used for the grand staircase, were supplied by the workshop of Ludwik Tyrowicz, sculptor and professor of graphic arts in Lwów. The interiors were dominated by art deco style. Equipped with wooden key-operated elevators and central heating—a rarity in the 1930s—the hotel was ahead of its time. In his letters, Kiepura explained that, due to his busy schedule abroad, he entrusted the running of the hotel to his parents: “I am building a hotel in Krynica: 200 rooms, a theater hall, a restaurant, bathrooms, telephones in the rooms, two elevators – in short, luxury. It will cost $160K, financed from my money and some loans. I am doing this for our parents, and it is also a safe investment.”

On Christmas Day 1933, the Palace Hotel Patria welcomed its first guests through its revolving doors. Kiepura delivered the promised publicity, and soon the cultural and political elite flocked there: artists, writers, statesmen, military officers, stage stars, even royalty. According to legend, Princess Juliana of the Netherlands and her husband, Prince Bernhard, checked in under false names, though their presence in Krynica soon became public knowledge. Other frequent guests included Hanka Ordonówna, Eugeniusz Bodo, Jadwiga Smosarska, novelist Tadeusz Dołęga-Mostowicz, General Bolesław Wieniawa-Długoszowski, comedian Adolf Dymsza, La Scala conductor Antonio Sabino, tenor Stefan Skupniewski-Belina, Kiepura’s brother Władysław, and, after her 1936 marriage to Kiepura, Martha Eggerth. They attended balls, lavish receptions, and operatic concerts in the hotel’s halls.

The outbreak of World War II abruptly ended the carefree artistic life of Krynica – once dubbed the “Polish Davos.” Kiepura and Eggerth fled to the United States, and the hotel fell into the hands of the German occupiers. Though the building survived, it never regained its former prestige. After 1949, “Patria” was nationalized and converted into a sanatorium for the working class. Much of the interior was stripped and replaced with cheaper furnishings. Kiepura fought for compensation, which, according to some sources, he received in the 1960s, though Eggerth never confirmed this.

Although modified over time, the building continued to draw visitors with its association to Kiepura and the unique architecture. In 1973, director Janusz Majewski used its interiors as the set for “Jealousy and Medicine,” based on Michał Choromański’s pre-war novel, with music by Wojciech Kilar and leading PRL-era cast including Mariusz Dmochowski, Andrzej Łapicki, Ewa Krzyżewska, and Włodzimierz Boruński.

Wyświetl ten post na Instagramie

After 1989, “Patria” became the property of Krynica-Żegiestów Spa. In 2004, the 93-year-old Martha Eggerth sought to reclaim the hotel and establish a foundation in her late husband’s name, but the following year the Ministry of Infrastructure deemed her claim unfounded.

Today, the once-fashionable spa fails to capitalize on “Patria’s” potential. The building stands neglected, slipping into ruin. Since its inclusion in the register of historic monuments in 2013, any renovation would require the oversight of a heritage conservator. Today, the only reminders of Jan Kiepura are a commemorative medallion in the corridor, installed at the initiative of Bogusław Kaczyński, and the piano he once played, around which children now romp. Each year, on August 9, Krynica hosts the Jan Kiepura Festival, now in its 58th edition, with concerts, galas, and artist meetings across town. But “Patria” is no longer among the venues. It remains to be seen if the hotel’s halls will once more echo with operatic arias, keeping alive the memory of the legendary Polish tenor.