Three Poles conquer the Opéra Bastille

Three Poles conquer the Opéra Bastille

The alarm clock at five in the morning tore me out of a deep sleep. I love travelling, but these early wake-ups are killing me. Why am I doing this to myself? – I thought, but a moment later I remembered I was flying to Paris for “Aida,” and with that slightly improved attitude I dragged myself out of bed and made it to the airport. At least I wasn’t alone in my early-morning “suffering.” The plane was packed to the last seat. Luckily, I had a window spot and managed to fall asleep again before takeoff. The trip passed unnoticed.

This time I reached the hotel well before the performance, with enough time to prepare leisurely for my first visit to the Opéra Bastille. Until then, I had only been once to an opera in Paris – at the historic Opéra Garnier. Both venues operate under the banner of the Opéra national de Paris. The older, monumental 19th-century building (1875) now serves mainly a representative function and hosts ballet performances as well as smaller opera productions. The newer one, opened in 1989, is primarily devoted to opera. From the outside, the Opéra Bastille doesn’t radiate much beauty – in fact, its sheer scale is somewhat overwhelming. Built of glass, metal, granite and aluminum, it was meant to embody the idea of the “democratization of culture.” It was designed by the Canadian architect Carlos Ott, with the intention that opera should be accessible to everyone, not just the elite.

The doors open roughly 45 minutes before the performance. After passing through a metal detector at the security, you enter a very modernist foyer. Just inside, there’s a stand selling merchandise, recordings and books on opera; ushers loudly advertise programs, turning it into a small performance of its own. The entrances to the auditorium are one floor up – this is where the main foyer is located, with bars serving drinks and snacks. You can get there by elevator or stairs.

Several passageways – so-called airlocks – lead into the auditorium. Each passage is fitted with two sets of doors, effectively sealing off any noise from the outside once the performance begins. Both the stage and the audience area are striking, not so much for their beauty as for their sheer scale. This is the largest opera hall in Europe, with a capacity of 2,750 seats. The stage is also among the biggest and most technologically advanced. The seating layout, shaped like an amphitheatrical fan, eliminates the traditional boxes and divisions into zones – every audience member has a direct line of sight to the stage and a clear view of the conductor. There are no columns, obstructing railings, or walls. The floor’s slope and segmented levels ensure that each viewer’s sightline passes above the head of the person in front. This embodies Carlos Ott’s principle of la salle démocratique – the “democratic hall.” The seats are exceptionally comfortable, with lumbar support that naturally fits the curve of your back, and armrests set at just the right height. All this makes even the longest performances enjoyable without fatigue. Stepping into this “hall” for the first time, I momentarily felt as though I’d found myself in Warsaw’s Torwar arena – such is its sheer, overwhelming scale.

The beginning of the performance – and of each subsequent act – is announced by an insistent sound of bells blasting from the speakers, so persistent and unpleasant that after a few minutes you feel like running away. The ringing goes on for a good five, maybe even seven minutes without interruption, and it turns out to be a very effective way to deal with unruly or slow-moving audience members.

The performance of “Aida,” directed by Shirin Neshat, which happened to take place on the 212th anniversary of Giuseppe Verdi’s birth and was streamed that evening on the Paris Opera Play platform, was produced in co-production with the Salzburg Festival. I had already had the chance to see it a few years ago. In Neshat’s interpretation, this is a completely different “Aida” from the one most of us are used to. The director places strong emphasis on showing both sides of the war, allowing us to see its consequences through the eyes of the defeated nation. In the context of today’s wars – above all Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, but also the ongoing conflict in Gaza – this interpretation feels particularly relevant.

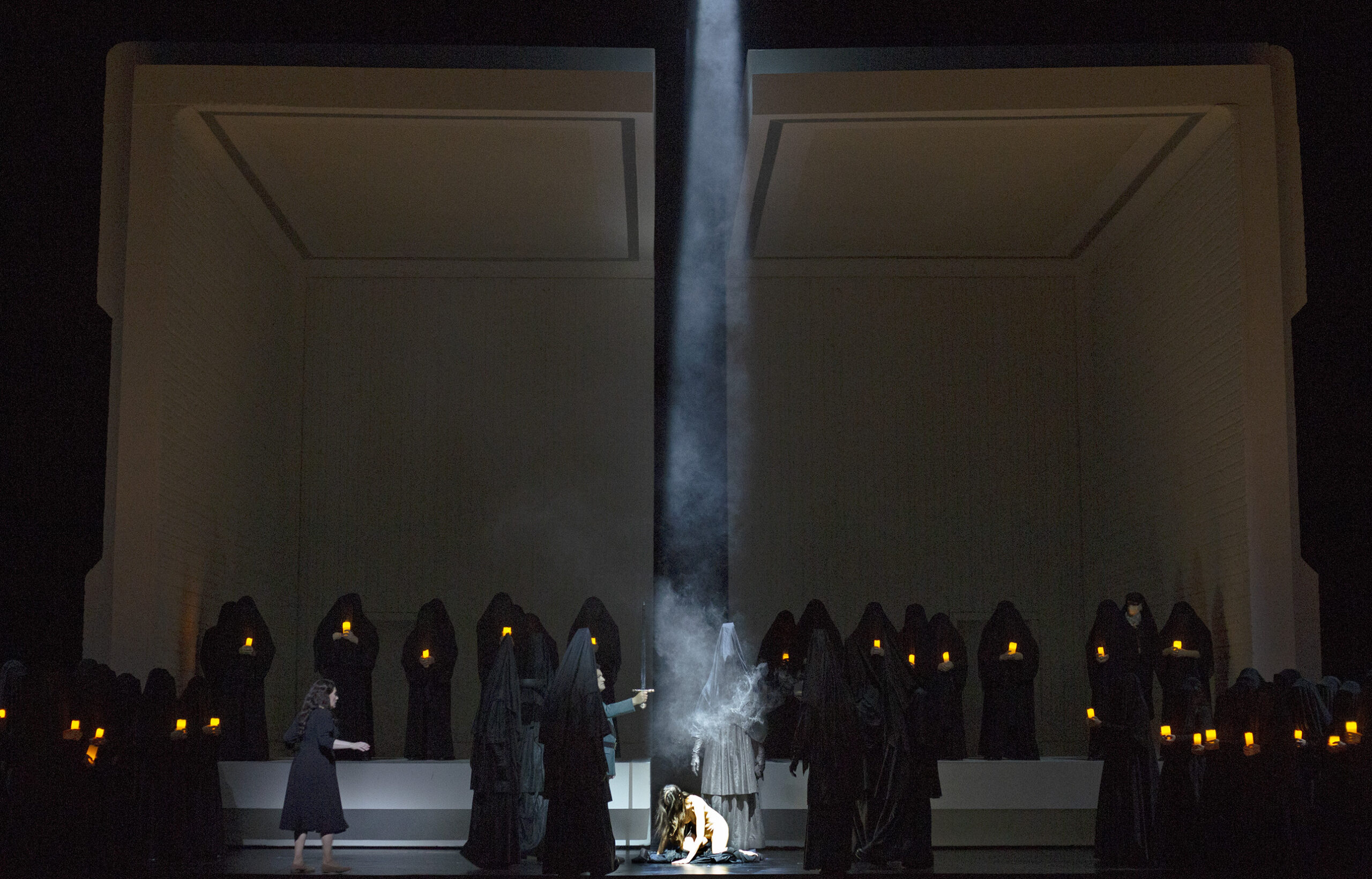

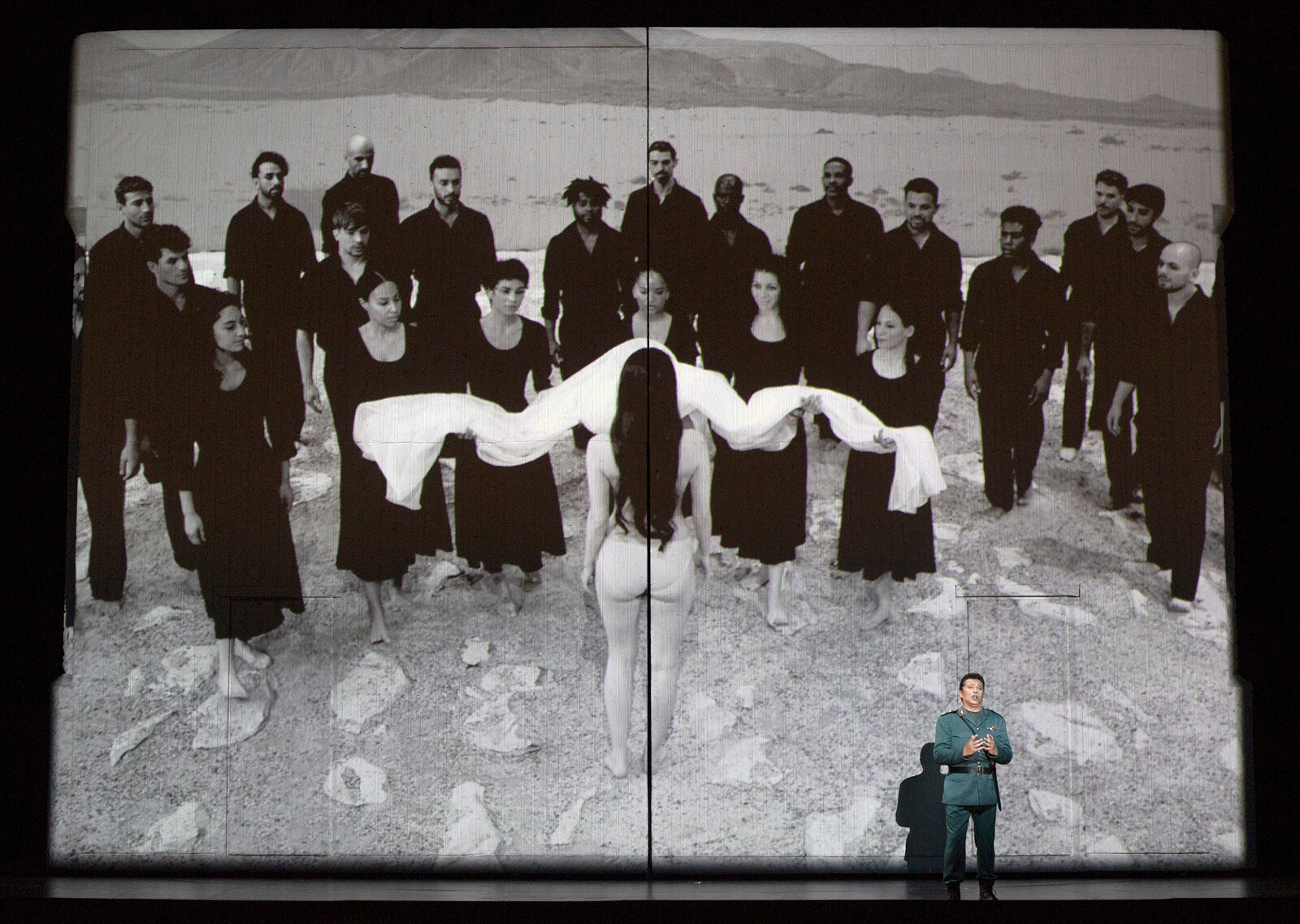

The central element of the stage design, created by Christian Schmidt, is a massive cube placed in the middle of the stage on a turntable, allowing us to view it from all sides. Depending on the scene, it opens into two parts or becomes an enclosed space for more intimate episodes. The side walls are used for film projections by the director herself. Instead of lavish scenery, we get coldness, light, and monumental emptiness. Instead of crowds of extras and grand mass scenes – lonely figures and oppressive ritual. The monumental space of the Bastille turns into a temple of the system, where every emotion is regulated, and feeling itself becomes an act of rebellion and protest.

Neshat presents a world in which women – whether among the victors or the vanquished – remain subject to male authority. This is particularly evident in a scene in Act II: instead of the usual ballet for Princess Amneris, the scene depicts a woman challenging male dominance. It’s a brilliantly staged confrontation of forces – the men bring in a red dress that Amneris refuses to wear, yet in the end she gives in, because even with the support of her loyal attendants, she cannot withstand male domination.

In Act III, Aida, under emotional pressure and manipulation from her father – who plays on her sense of duty and patriotism – agrees, against her own feelings, to extract from Radamès the secret of the war strategy. Amonasro exploits her love to achieve his goal: to regain power and avenge the loss of his homeland. The famous triumphal march is stripped of all triumph, shown instead as a vision of humiliation, defeat and the loss of freedom for the Ethiopians. It begins with the ritual killing of a virgin as a sacrifice to the gods in thanks for victory, and ends with the slaughter of captured prisoners. Only Amonasro survives.

An important element of both the stage design and the narrative are the video projections – focused primarily on the faces of the oppressed nation: their suffering, pain, fear, and uncertainty. They form a counterpoint to the conqueror’s arrogance and triumph. At times, they serve as a visual commentary to the arias – such as in the Nile scene, where Aida is accompanied by a projection of women washing clothes in the river: an everyday scene, yet full of symbolic power. In the interludes between scenes, the projections show the murdered and imprisoned – becoming a testimony to crimes and a reminder that both secular and religious power can be equally ruthless. Dramaturg Yvonne Gebauer weaves these threads into a coherent structure, giving the production a sense of logical and emotional continuity.

I was particularly lucky that this performance (with a double cast) featured as many as three Polish artists: soprano Ewa Płonka, bass Krzysztof Bączyk and tenor Piotr Beczała, who clearly stood out both vocally and dramatically. In his interpretation, Radamès – the commander and hero of a great war – also appeared as a man torn by his feelings for Aida. It is a hopeless, unfulfilled love, caught between duty to his homeland and a passion he cannot express, and complicated further by Amneris’s unwanted affection. Beczała handled all these challenges – dramatic, emotional, and vocal – brilliantly.

Vocally, his performance was nearly flawless. In one ensemble, he lost control of his voice for a split second, but that minor lapse was insignificant in the overall picture. “Celeste Aida” was superb: long, beautifully shaped phrases, effortless reach to the top notes, noble pianissimi and perfectly finished endings. Also in his ensembles with Aida, Amneris and in the choral scenes, his voice carried confidently and clearly – formed a solid backbone of the production. Whether in dramatic or lyrical moments, he maintained the same consistency and radiance. Together with Ewa Płonka, he delivered a stunning final duet – a masterclass in delicate, piano singing, whose subtlety and tenderness were truly moving.

Ewa Płonka, who replaced Saioa Hernández that evening and thus advanced her Paris debut by a few days, sang the title role far better than she had last season in Kraków. Her soprano, warm in colour and with strong projection, sounded stable and well-supported. In “O patria mia,” I missed a touch more dramatic charisma and emotional fullness – especially in the upper register – and, what remains her main weakness, a more elegant finishing of phrases. It felt as if that final dot over the “i” was missing. In the rest of the performance, however, her interpretation was convincing, and at times even very good – her acting, though occasionally too expressive, appeared natural on such a large stage. The final duet with Beczała will stay with me for a long time.

Eve-Maud Hubeaux, as Amneris, needed a little time to spread her wings fully. In the first act, her somewhat metallic voice occasionally struggled to cut through the orchestra, especially in the lower registers. It’s a very bright mezzo-soprano, and personally, I tend to prefer darker, more full-bodied voices in this role. Nevertheless, in terms of acting – and later also vocally – Hubeaux delivered a strong performance. Her Amneris was convincing, powerful, and full of inner tension, and in the second half of the performance she was able to beautifully shape her phrasing and create a character that truly held the audience’s attention.

In the role of Amonasro appeared Roman Burdenko, endowed with a warm baritone of very pleasant timbre. With great temperament, he portrayed the father and king of the Ethiopians – a proud figure, yet not devoid of emotion and humanity. Among the basses, Krzysztof Bączyk (the King) and Alexander Köpeczi (Ramfis) stood out with their dignified, resonant voices, which filled the vast space of the Opéra Bastille beautifully.

Special praise must go to the chorus, prepared by Ching-Lien Wu, which sounded magnificent – balanced, majestic, and perfectly controlled. The temple scene, during which Radamès is chosen as commander of the Egyptian army, was pure perfection – it literally gave me goosebumps. I had never heard this scene performed so brilliantly. The women’s chorus in the scene with Amneris, the triumphal march and the final judgment of Radamès – all these moments confirmed that the chorus was not only a key protagonist but also an outstanding partner to the soloists. Simply superb.

Overseeing the entire performance was the Italian maestro Michele Mariotti, who not only provided excellent support to the singers but also shaped a cohesive and deeply considered musical interpretation. The orchestra played superbly – the balance between the pit and the stage was ideal.

The acoustic qualities of the Opéra Bastille’s grand auditorium are quite distinctive and take some getting used to. During the first few minutes, I thought the sound was too soft and the hall too vast, but that impression quickly faded, and the overall musical and vocal experience proved excellent. Perhaps the sheer size of the venue forces singers and directors to position much of the action along the “front line,” near the orchestra pit? I’ll check that next time.

What to know before attending a performance at the Opéra Bastille:

- Travel: From Poland, it’s easy to reach Paris with both budget and regular airlines. From Charles de Gaulle or Orly airports, you can take the RER train (ticket around €13 one way).

- Performance: It’s best to arrive a bit early – the closer to curtain time, the longer the security check lines.

- Hotels: If you’re looking for more affordable stays, check the city’s outskirts, especially near the airports.

- Programs: €15.

- Bar: A glass of champagne: €15.

- Standing tickets: About an hour before the show, standing and “strapontin” (folding seat) tickets are available for €5–10.

- Surtitles: Displayed on a board above the stage and on side screens; available in English and French.